Cucklet Delf: a Limestone Pulpit for Plagued Times

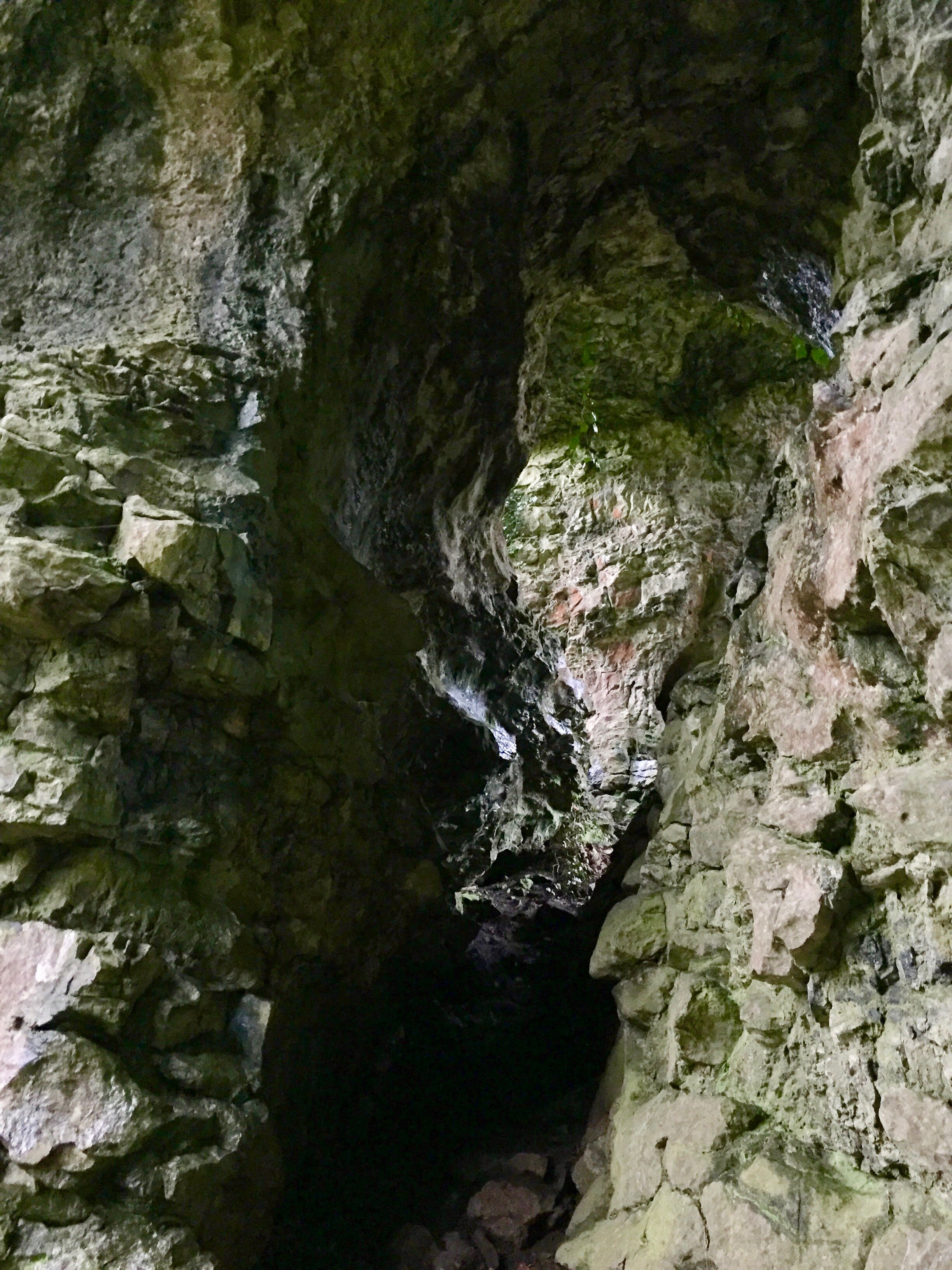

The Delf is a natural valley that runs south from the idyllic Peak District village of Eyam. A short way down it is Cucklet Delf (which I’ve also seen spelt ‘Cucklett’ or ‘Delph’), a beautiful limestone craglet that forms a cavern with two large arches.

From 1666, the larger of two archways became the pulpit for the twenty-seven-year-old village rector, William Mompesson. From here, he could preach into the valley and be heard by his congregation, gathered in disparate family groups on the opposite hillside. Throughout the outbreak of the plague, this crag — and, in fact, this whole section of the Delf — became the Cucklet Church.

Directions

It’s not far to the Delf from Eyam, but it can be muddy. Walk down New Close, opposite Eyam Hall, and take the first left down Dunlow Lane (after the entrance to the car park). When Dunlow Lane twists round to the right, go ahead instead towards a lush, green footpath lined with dry stone walls. A sign post here indicates that you’re on the right track.

You’ll go past an enclosure with three chicken coops. (Yes, they’re occupied.)

Right after, go through a gate and over a stile to get into the field.

You’ll find another signpost down the slope with a hump behind it, and from here you just need to follow the worn path a little more to find the archways in the craglet.

Both slopes are now so overgrown that it’s hard to imagine the valley as an amphitheatre populated by a diminishing congregation, but you can have a go at projecting your voice into the trees in any case.

Eyam’s Plague: a Brief History

The plague was unleashed in Eyam when the village tailor, Alexander Hadfield, ordered cloth from London in the Summer of 1665, at the height of a plague outbreak in the capital. The fabric arrived damp and, on being hung up to dry in front of the fire by Hadfield’s assistant, George Viccars, fleas infected with the deadly bacteria were unleashed. Viccars was the first to die, quickly followed by his two stepsons, a neighbour, and Hadfield himself.

Twenty-three more people died in October, but the rate of deaths slowed over the Winter and no precautionary measures were taken. It was only when more starting falling victim to the plague in Spring 1666 that the new rector, Reverend William Mompesson, decided to close the village (though not before he sent his own children away to Sheffield).

As well as putting the whole village into quarantine, Mompesson and Thomas Stanley, the previous minister, ruled that all public gatherings were to cease, including church services, and they decreed that all families should bury their own dead to prevent cross-contamination between families.

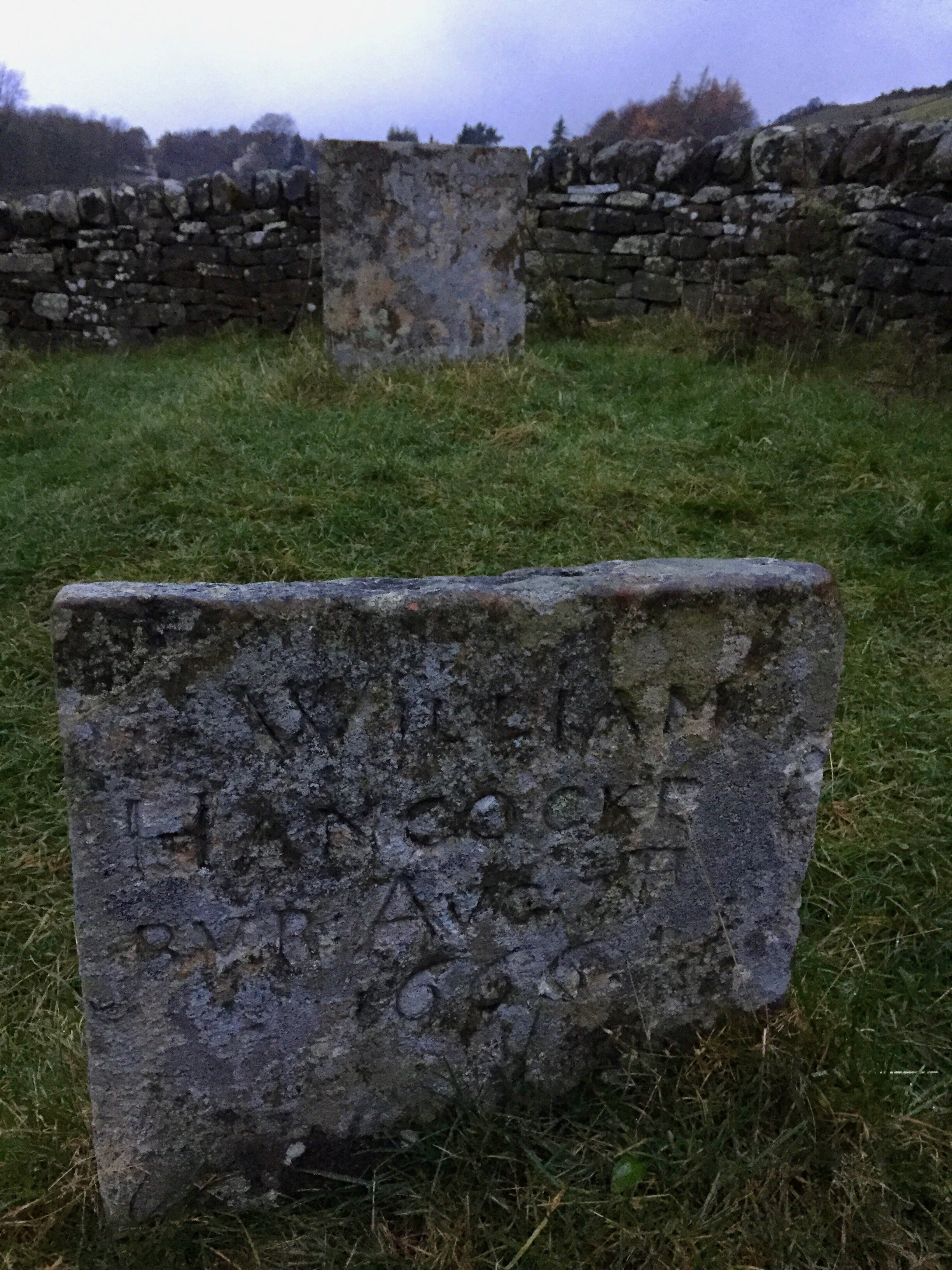

It’s for this reason that there are many small graveyards around Eyam. One of the most famous is the Riley Graves, named after the Hancock family farm: here, Elizabeth Hancock buried six children and her husband within eight days, while she survived. Sadly, it was probably her neighbourliness in helping bury the dead of other families that brought the plague to her own.

So it was that the church services were conducted in the open air until December 1666. By then, the plague had ravaged the village for fourteen months: it is estimated that between fifty and seventy-five per cent of the villagers died. In London, where the outbreak killed around 100, 000 people (15% of the capital’s population), it took the Great Fire to halt the disease.

Each year, a remembrance service is held at Cucklet Delf on ‘Plague Sunday’, the last Sunday in August.

Cucklet Delf in 1896.

Eyam Churchyard

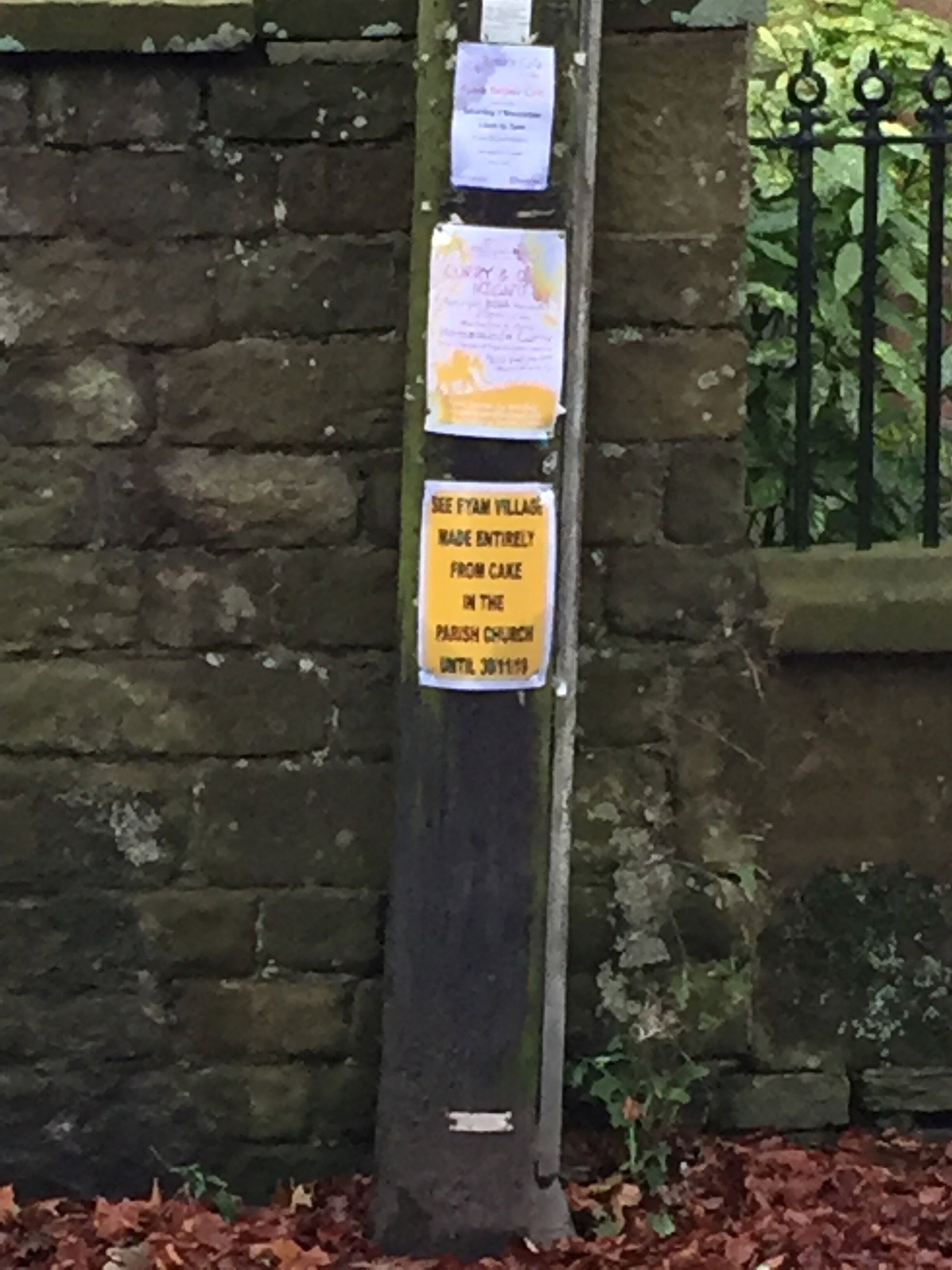

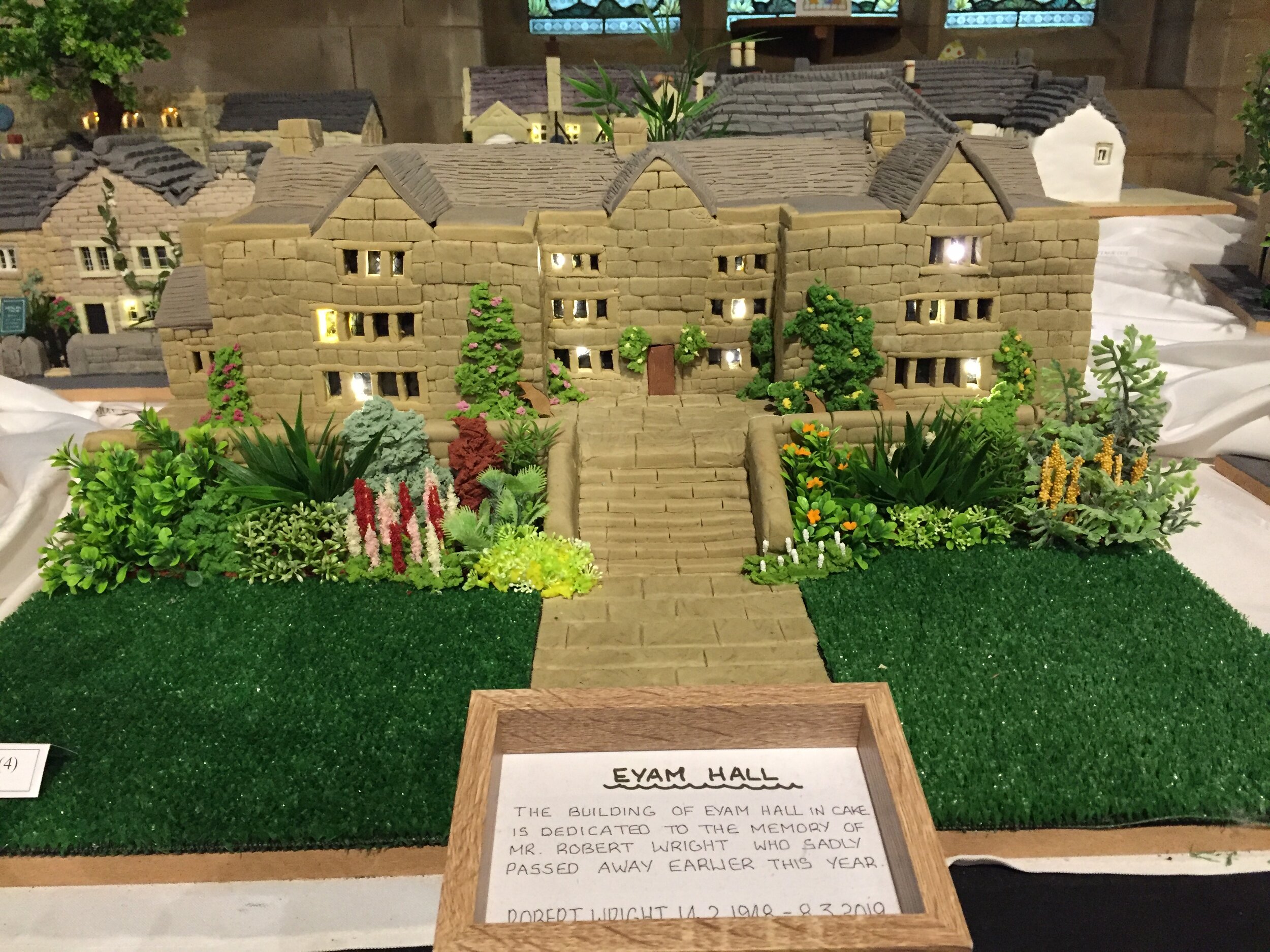

It was hard to miss the fact that something was happening at the church last year.

We were not disappointed:

There’s lots to see inside the church (a section at the back where you can buy the sort of tourist tat that I adore. Eyam bookmark? YES PLEASE), but churchyard is full of even more history, including a Celtic cross (which is missing a segment), an optimistic Eighteenth Century sundial, and Catherine Mompesson’s grave. She was the only plague victim to be buried in the churchyard, a reward for her loyalty for staying by her husband’s side. That’s not her spooky grave below: it’s just a spooky grave.

Further Walks

Unsurprisingly for a village in quarantine, many of the historical sights are far out from the centre of Eyam, and separate from each other too, without an obvious route connecting them all. That makes them perfect for self-isolaters in need of a heritage fix.

Some excellent places to venture around Eyam: 1 Cucklet Church; 2 the Boundary Stone; 3 the Riley Graves; 4 Mompesson’s Well; 5 Ladywash Mine; 6 Sir William Hill.

It’s a small, straightforward trek uphill from the village centre to the Riley Graves, and from here the views are spectacular.

The Boundary Stone, meanwhile, is South-East down the hill towards Stoney Middleton. (Definitely get some food from the Tollbar fish and chip shop in Stoney Middleton if you head that way.)

Mompesson’s Well still runs, and you can find it North-East of Eyam Hall, a steep trek out from the village. You can park close by here, potentially on your way to or from the village, but there are other good walks around here: Ladywash Mine is nearby (that’s the strange chimney you can see from here), and there’s a good footpath which takes you through a field, over a stoney road and up Sir William Hill to a trig point that has incredible panoramic views. (Some hate the radio mast, but I like it.)

Newsletter

At the end of every month, I send out a newsletter. It features a quick blog round-up, behind-the-scenes details, progress updates, pictures and oversharing. You can sign up here.