A Virtual Tour of South Georgia

At the beginning of November, as the first polls closed in the US election and the world began to repeatedly click ‘refresh’ on news sites that automatically refresh anyway, an entirely unrelated headline kept cropping up: ‘A68 iceberg on collision path with South Georgia,’ stated the BBC and others, accompanied by a picture of the massive berg, floating like a disembodied butler’s hand and pointing an accusatory finger at the island itself.

An image from the British Antarctic Survey that accompanied the news reports, showing the ‘pointing finger’ of iceberg A68.

‘Where the hell is South Georgia?’ I wondered (showing that I had no knowledge of the details of Ernest Shackleton’s escapades in the (very) South Atlantic Ocean, and that I hadn’t paid enough attention to the specific locations of David Attenborough’s penguin watching). At least one article contained an image of a cute, Nordic-looking settlement with a dramatic mountainous background, and I was intrigued. But when I finally went to Google Maps, I was somewhat surprised at what I found.

A panoramic photograph of Grytviken, formerly the largest whaling station on South Georgia. Crops of this kind of picture were originally used in some of the newspaper articles. Click to be taken to the larger original on Wikipedia.

A Beginner’s Guide to South Georgia

There are no cute settlements on South Georgia. It’s a beautifully inhospitable, rocky mass, 170km long and 40km wide, and completely stranded at the southernmost reaches of the Atlantic Ocean. It’s as close to the Antarctic Peninsula as it is to South America, and 57% of its surface is covered in glaciers. They pour down the island’s steep valleys into the sea like ice chutes.

The spine of the island is the Allardyce mountain range, on which the highest peak is Mount Paget at 2934 metres (and first climbed in 1964). The mountains, thought to be a continuation of the Andes, protect the north-eastern coast of the island from the harshest winds that come in from the Antarctic, and so the shores on this side are never ice bound. This makes the island a haven for wildlife: gigantic elephant seals, cute fur seals, a range of penguin species (including Macaroni, King and Gentoo), albatross, petrels and imperial shags are all non-permanent residents on the island. Except for scientists on long research assignments, no humans live here. But the island used to be very busy indeed: the protected north-eastern coast and the abundance of wildlife made South Georgia perfect for some uniquely human endeavours.

Stromness

I zoomed in on South Georgia to find the cute villages that I felt the newspaper articles had promised. As I moused down into the named harbours, shop names appeared (KFC, an Apple Store, Lidl) and I was amazed that this forlorn place would have such conveniences, especially when I went further and, well, everything’s just brown. Really, really brown.

The brown buildings of Stromness.

Of course, the shop names were a joke: some digital littering by bored people. The settlements had long been abandoned. Naturally, I clicked on the street view icon and, as luck would have it, there was a photo sphere.

Oh my God.

Hundreds of seals and pups populate a beach of splintered rock. The animals cluster round the rusted propellors from dozens of long-lost ships. There are old masts, too, with seals resting on them, basking. A line of wooden posts stretches from the water’s edge and into the distance, bissecting the beach. Each post says ‘KEEP OUT’, and behind is a mass of seals and, behind them, the rusting, fragmented structures of an industrial ghost town. Some of the animals are so large that they might be elephant seals. The mountains rise up in the background, and a small boat waits patiently in the bay.

This is not what I expected.

Husvik

From above, there is little to differentiate the brown remnants of Husvik from its neighbour, Stromness, except for its long, dilapidated pier. Of course, there is no Starbucks.

Husvik, in a bay to the South, promised a lot too. There are two photo spheres here, close to a small cluster of newer, maintained buildings that are separated from the industrial remnants by a river and about fifty metres. One sphere is taken behind what I can’t help thinking is the toilet. Again, the small boat lurks in the bay. The other photo sphere shows a repurposed harpoon gun, fixed into the earth and looking out to sea. Huge drums dominate the scene, and behind them are the blank-eyed husks of huge buildings, with some sort of scaffold structure beyond. There is life in the scene, though: the pleasing amorphous shapes of seals lie in the grass.

Leith

Leith is the northernmost abandoned settlement of the three on the promontory I looked at first. The internet had placed four non-existent businesses on top of the brown buildings, and I wasn’t hopeful that there’d be much to see.

Fortunately, I was very wrong. There are two astonishingly beautiful photo spheres, courtesy of a drone, one looking at the settlement from above the bay, and the other over the wrecks of the buildings themselves. If you click only one link from this blog, click one of these two: it’ll be the best click of your day, especially if you’re not on your phone.

It’s these photo spheres that really give an insight into the scale of the operations on South Georgia. By now, I’d fathomed that this was an island dedicated to the mass capture and slaughter of whales. Here, the southernmost building is enormous, and so is the ramp up which whales would be winched.

Leith was clearly the largest of the three whaling stations in this part of the island, but there were four more bays dedicated to butchering whale carcasses. Leith was bigger than all of them.

Grytviken

I still hadn’t found the location of the deceptive Nordic-esque scene shown in the news, however, and sought it out. Grytviken was the site of the first permanent whaling station on South Georgia. It opened in 1904, the brainchild of Carl Anton Larsen, a Norwegian Antarctic explorer, after whom the Larsen Ice Shelf (the one that spawned Iceberg A68) is named.

Grytviken is on the left, in the middle of the bay. Miraculously, the labels here are accurate. The peninsula opposite Grytviken is King Edward Point, which is a research station and the South Georgia base for the British Antarctic Survey.

To my amazement, in Grytviken, you can virtually walk around a lot of the area, imagining that you’re amongst the tourist-adventurers who have just hopped off a National Geographic ‘expedition’ (these special cruises will cost you from $18k to well over $56k per person). There are actual tourist sites here: a museum, the cute church from the press photographs, and the grave of Ernest Shackleton.

Grytviken is by far the most accessible of the former whaling stations, hence people being able to walk around freely enough to give us a street view. The others are deemed too dangerous for this level of access: many structures look set to collapse, and apparently there’s asbestos floating around in the air there.

Grytviken is also linked by road to King Edward Point, the base of the British Antarctic Survey on South Georgia. It’s thanks to their staff that we have access to such incredible photo spheres as this:

A drone captures a 360 degree view from above the BAS base at King Edward Point. The settlement of Gritviken and the graveyard where Shackleton is buried are both in view.

Whaling around South Georgia

There were three other whaling stations on the island, but they were significantly smaller. Some existed mainly to aid floating factories, rather than to conduct operations ashore. There are no streetview walks to be had there. Some are even difficult to find from above.

A map showing the locations of the seven whaling stations (beige dots) and the two modern research bases (black dots).

Given the scale of whaling across the globe in the 20th Century, it’s a miracle the whale species we have survived into the 2000s. When Carl Larsen suggested South Georgia as a base for whaling operations in 1902, it was because the seas in the Northern hemisphere had already been horrendously depleted.

Whalers found the South Atlantic as plentiful as Larsen had promised: the various companies based on South Georgia slaughtered 175,000 whales here. After being harpooned, whales were towed back to harbour and left to die on the shore (if not already dead). Blubber was then stripped from their carcasses and boiled. Such was the “success” of these operations that the price of whale oil dropped substantially at the height of production.

The growing scarcity of the whales eventually led to the operations ending in the 60s due to a mixture of environmental and financial factors. The last whaling activity took place in Leith in 1966, though illegal and unregulated fishing obviously continued. To this day, the oceans around South Georgia are regularly patrolled and monitored.

Whalers at Grytviken. It was due to commercial success here that other whaling companies were drawn to South Georgia. At the time, the glycerin in whale blubber was the main ingredient in soaps and lotions and provided the base for fuels for oil lamps and boilers.

A blue whale on a flensing platform at Grytviken in 1917. Whale blubber was an extremely important commodity during the First World War, as it provided the nitroglycerin for explosives. The meat was also relatively cheap and in demand. Grytviken was home to 500 people (workers and their families). 53,761 whales were slaughtered here, producing 455k metric tons of whale oil and 192k tons of whale meat.

An Eco-System in Recovery

As if to compensate for its shameful part in almost eradicating the most amazing mammals on the planet, South Georgia is now a conservation success story, although that, too, involved a lot of bloodshed: the whalers had accidentally brought mice and rats with them, as well as reindeer (on purpose), and these animals devastated the native wildlife, which includes birds that are found nowhere else. After a period of culling, along with the eradication of invasive plant species, too, the island was finally declared rat-free in May 2018.

South Georgia is now renowned for having the greatest concentration of mammals and sea birds on the planet, and conservation is taken very seriously. A Marine Protection Area expands 200 miles around the island and it is rigorously policed and managed. Helicopters and hot air balloons aren’t allowed, and visitors have to go through decontamination procedures before they’re allowed off their ships. Tourists and vessels are only allowed to visit very specific locations, and even then, movements may be limited to certain areas. Recently, more blue whales have been sighted or heard around the island, making conservationists hopeful that they’re finally returning to an area where, at one point, up to 3000 of them were killed every year.

The coat of arms of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands celebrates the wildlife, featuring an Antarctic fur seal and a macaroni penguin, but the reindeer crest is a bit rich/very outdated now, seeing as thousands of them were culled in 2013. The coat of arms was granted in 1985, which somewhat explains both the reindeer, and the macho motto, 'Let the lion protect its own land.' British ownership of South Georgia is obviously disputed by Argentina, and there were two battles there in April 1982 during the Falklands War.

Top Things to do in Digital South Georgia

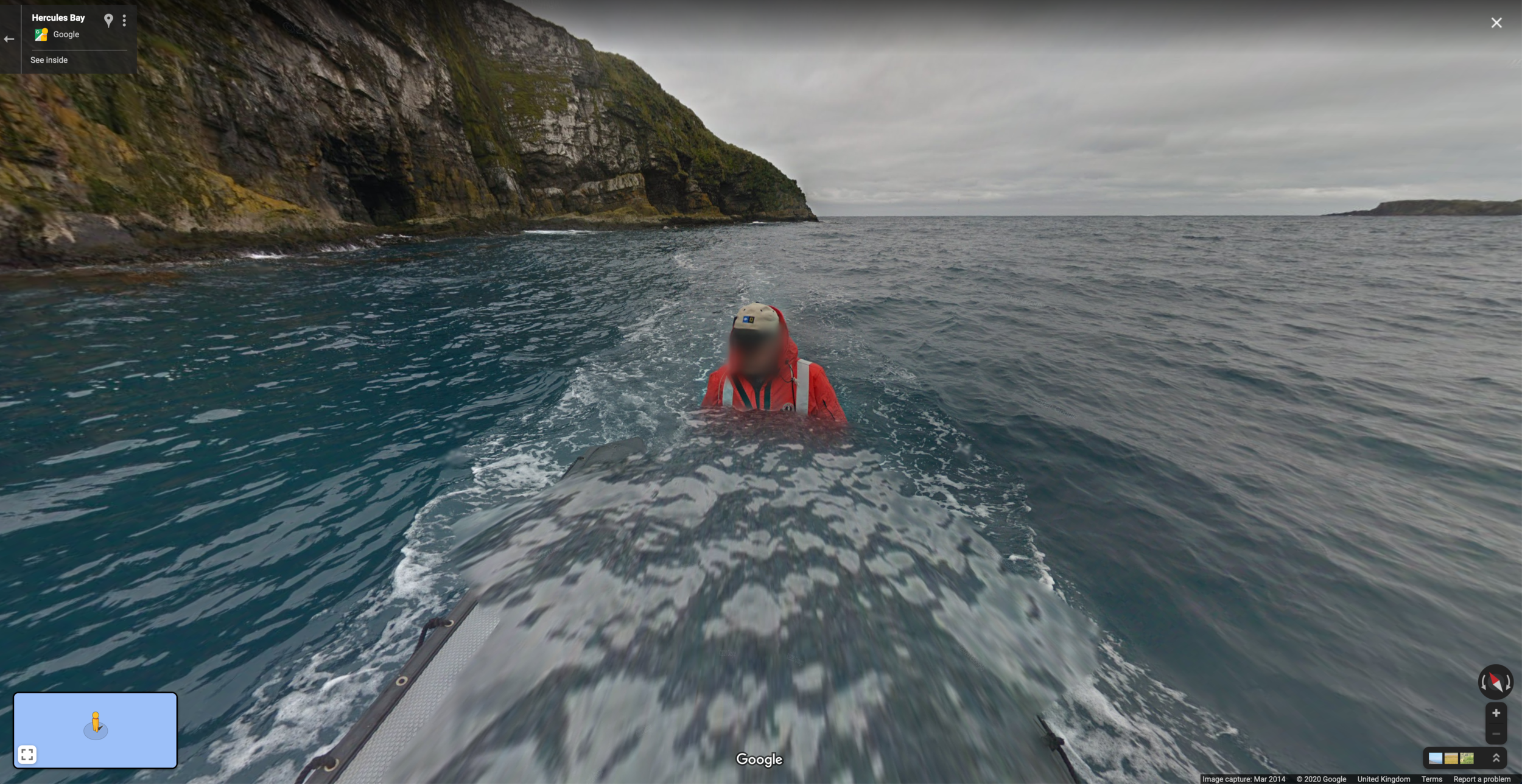

After taking in the sights at the dilapidated whaling stations, digital explorers can take a dinghy trip right round Hercules Bay, click by click, seeing the caves, a waterfall, groups of posing penguins, and seals curled up like neat tog turds

Or why not walk up and down the wooden stairs and footpath on Prion Island, past nesting albatross and relaxing fur seals?

Be thankful you can’t smell anything through the internet when you take a look at the King penguin rookery in St Andrew’s Bay!

Dither over all the things you can look at on Bird Island:

After a long trek of mouse clicks, just relax with friends, taking in the view from Stenhouse Peak.

On your way home, be sure to explore the view from and inside different ships:

Larsen Harbour from a Ponant cruise (the left-most blue dot) or hop aboard the German research icebreaker "Polarstern" and take a look round the research fleet’s largest vessel (all the other dots).

The Threat of A68

As for the gargantuan iceberg that cleaved of the Larsen-C Ice Shelf in 2017 and made news headlines in early November, it appears to be twisting its way up northwards and it will hopefully pass to the west of South Georgia and up towards warmer waters, where it will melt more quickly. If that happens, the krill that are feeding on the dirt beneath the berg will provide a plentiful food source for the protected animals in the seas around South Georgia.

If it passes close enough, perhaps it will appear on a photo sphere near you very soon. Sadly, though, more and more icebergs are sure to threaten the ecosystem of South Georgia in the years and decades to come.

A gif from the European Space Agency’s Copernicus Sentinel-1 images.

Collected data from Sentinel-1, showing the iceberg’s journey north.

Links and References

It’s only possible for us to virtually explore South Georgia in such an amazing way because of the photography of two people who worked for the British Antarctic Survey: you can find Alastair Wilson on Twitter, and read about his experiences on Bird Island on his blog; and you can see the wonderful photography of John Dickens on Instagram and via his Twitter account. Thank you to Alastair and John for giving others access to such an amazing and important place.

There is a lot more to say about South Georgia that there isn’t room for. For a good introduction and lots of beautiful filming, you can watch the official visitors’ guide, which is narrated by David Attenborough. That video is hosted by the Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (which is actually based in Stanley, in the Falkland Islands) and there’s a huge amount of interesting information to be found there. They don’t seem to hide any information about the island’s history, and you can find out more about the reindeer cull directly from them.

I didn’t want to go into too much detail about the whaling because it’s so bleak, but there’s a wealth of information out there for those who do. I stole some pictures and information from Rust and Ruin: The Downfall of Antarctic Whaling by Spiegel International, and there’s a good potted history of Whaling in the Southern Ocean here. You can even hear a first person account of whaling in South Georgia courtesy of BBC Sounds: Witness History: The Antarctic Whale Hunters.

I didn’t even go into the discovery of South Georgia, the competing claims, and the part it played in the Falklands War. For information on that, Wikipedia is a good first port of call.

I said ridiculously little about the climate emergency that is the reason for the iceberg threats to South Georgia. The same factors are responsible for the retreating glaciers on the island which constitute a growing threat to the ecosystem (see picture below).

There’s also a ton to say about the role South Georgia played in the exploits of Ernest Shackleton. Again, I refer you to Wikipedia for an overview of his utterly improbable Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-17. (Spoiler: this venture isn’t the reason Shackleton is buried in Grytviken.)

Lovers of geography and history alike might like this interactive map, hosted by BAS, though it’s stupendously slow. Similarly, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands are clearly on tectonic plate boundaries, but you can find out more about that at your leisure.

In fact, I said next to nothing about the South Sandwich Islands, though they’re very interesting in their own right, as volcanic islands inherently are. Here’s one fact: Mount Michael on Saunders Island (it seems silly that they have different names, when the island seems to only consist of the volcano) has a persistent lava lake, making it one of only eight volcanoes that do. This pleases the child in me, who thinks that all volcanoes should have lava lakes in a crater.

Information about the retreating glaciers can be found on the interactive map.

You can see Shackleton’s phenomenal route across South Georgia on this very slow map, and read about why he and two of his crew made this incredible journey on Wikipedia.

The lava lake of Mount Michael on Saunders Island, one of the South Sandwich Islands, sadly not visible due to the volcanic smoke.

Newsletter

At the end of every month, I send out a newsletter. It features a quick blog round-up, behind-the-scenes details, progress updates, pictures and oversharing. If you like the content I create, you can sign up here.